Turkey’s growing involvement in Syria recently reached a flashpoint with Israel, following Israeli airstrikes in early April that targeted three Syrian airbases Turkey was reportedly looking to make use of. The incident prompted rare official statements from Ankara regarding its operations in Syria: Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan told Reuters after the strikes that “Turkey has no interest in fighting any country on Syrian soil.”

A week after the conciliatory statement, Fidan revealed in an interview with CNN Turk that Turkey and Israel are holding technical-level talks to avoid “military confrontations” in Syria, as the new leadership seeks to establish itself following the fall of Bashar al-Assad.

Despite growing concern in Israel over Turkey’s entrenchment in Syria, Jerusalem appears to be left with few options to counter it.

“Ultimately, when it comes to Syria, Turkey simply cares more about it than Israel does, and invests accordingly. Israel’s interest in Syria is purely security-oriented,” Gallia Lindenstrauss, a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), told The Times of Israel. “That gives Ankara the upper hand.”

She added that US President Donald Trump’s backing for Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan further limits Israel’s maneuverability.

“President Trump made it clear in the last meeting with [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu in Washington that while he’s willing to help Israel with Turkey, Israel must make ‘reasonable demands,’” Lindenstrauss said.

“He’s pushing Israel to adopt a minimalist approach in Syria. To prioritize, Israel will have to insist only on its most critical red lines, like preventing Iranian arms transfers to Hezbollah through southern Syria.”

A history of support for rebels

Ankara’s ties with Syria’s new leadership date back several years.

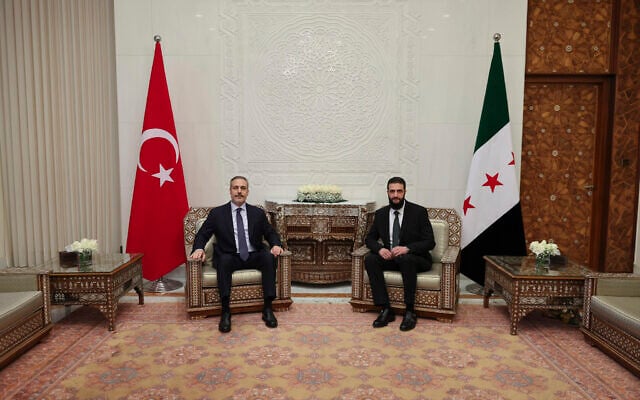

“Turkey was a friend to Syria and supported it from the start of the revolution — Syria will not forget this,” the country’s new leader Ahmad al-Sharaa said on December 22, 2024, during a joint press conference with Turkey’s foreign minister at the presidential palace in Damascus.

Before declaring himself president, Sharaa led the jihadist rebel group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra — an al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria. Sharaa cut ties with al-Qaeda several years ago and has sought to portray himself as a moderate since taking power, though Israel has expressed serious doubts.

While Turkey officially designates HTS and al-Qaeda as terrorist organizations, following US policy, and has never maintained formal diplomatic or economic ties with them, it has long been thought to offer varying degrees of support to Syrian rebel factions since the early days of the civil war in 2011.

Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan, left, sits with Ahmad al-Sharaa, formerly known as Abu Mohammed al-Golani, during their meeting in Damascus, Syria, Sunday, Dec. 22, 2024. (Turkish Foreign Ministry press service via AP)

“Turkey supported the full spectrum of Syrian rebel groups shortly after the civil war began, once it gave up hope for reform under the Assad regime,” said Lindenstrauss. “Anyone who fought against Assad received some level of Turkish backing — logistically, medically, and in some cases, militarily.

“While Jabhat al-Nusra wasn’t the main beneficiary, Turkey did have closer ties with other rebel factions,” she said. Such support was primarily coordinated by Turkish intelligence, led at the time by Fidan — now Turkey’s foreign minister.

“In [Fidan’s] recent December meeting with Sharaa, you could see that these people have known each other for years,” Lindenstraus said.

Turkey’s backing became very public following the swift success of the coup that ousted Assad. Turkey was the second country visited by Sharaa in his new role, following a trip to Saudi Arabia. According to a study by the Washington Post Institute, during the early months of the new government in Syria, Turkey led the pack in diplomatic engagement, holding 93 meetings, including official, business and humanitarian contacts. The second most active country, Saudi Arabia, had only 34.

Turkey’s interest in Syria has been clear since the outbreak of the civil war: to ensure a stable, friendly regime on its eastern border, one that could even potentially support Ankara’s security interests.

“Turkey has vast ambitions regarding Syria,” Lindenstrauss said. “It wants to block jihadist and Kurdish terrorism originating from Syrian territory. It even envisions Syria as a strategic outpost. On the economic front, Turkey doesn’t want to bear the cost of Syria’s reconstruction, but it does want Turkish companies to rebuild the country and reap the rewards.

“And then there’s the refugee issue: Syria hosted millions of refugees during the war, which has become a burning issue in Turkish domestic politics. A stable Syria is key to Ankara’s goal of returning those refugees.”

Syria seeks support amid economic ruin

As Syria emerges from over a decade of devastating civil war, its new leader finds himself ruling a nation that is exhausted, economically and socially. Sharaa rose to power quickly following the fall of Assad, but he now leads a country that is desperate for external support to maintain stability and rebuild.

One of Sharaa’s most consequential moves so far has been a public decision to end Syria’s primary source of income under Assad — the production and export of the drug Captagon — citing religious and moral reasons, as Islam prohibits narcotics.

According to a 2023 study by the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks, a Canada-based research institute run by Syrian expats, the Captagon trade had in recent years generated up to $10 billion annually for the previous regime.

Now, with that revenue gone, Sharaa is seeking financial backers and strategic allies to keep the economy afloat and maintain military control, especially given Syria’s complex sectarian landscape, and the fact that his ascension to power did not come through democratic means.

Israel, however, remains concerned about the military aspect of Turkey’s deepening involvement.

Just a week after Assad’s ouster, on December 15, Turkey’s defense minister stated that Ankara was ready to provide military assistance to Syria’s new government if requested. During a visit to Turkey on February 4, Sharaa declared, “Syria and Turkey share a long history. Today, we announce that these ties are becoming a strategic partnership across all areas.” On the same day, Reuters reported that the partnership would include a defense alliance, Turkish-led training for the new Syrian army, and even Turkish airbases on Syrian soil.

Despite these developments, there has yet to be visual confirmation of Turkish troops inside Syria, unlike the Russian presence under Assad, which was well-documented and which currently endures, at a reduced scale, at Hmeimim Air Base.

Lindenstrauss noted that the full details of the Turkey-Syria agreement have not yet been released. “The fact that there’s talk of a security pact between Syria and Turkey, but no official publication of its terms, indicates sensitivity on both sides,” she said.

US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters stand guard at Al Naeem Square, in Raqqa, Syria, Monday, Feb. 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Baderkhan Ahmad, File)

An alliance with challenges

Syria’s growing partnership with Turkey is proving to be a complicated balancing act domestically. A significant point of contention lies in eastern Syria, where Kurdish-led forces known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) have controlled approximately 40% of the country’s territory in recent years. On March 10, Sharaa signed a landmark agreement with the SDF’s leadership to integrate their autonomous administration into Syria’s new government structures and military.

The move represents a significant shift but will likely stir friction with Ankara. Turkey fundamentally opposes any form of Kurdish autonomy in Syria due to fears it could embolden its Kurdish population and lead to internal unrest.

“Turkey wants ‘good Kurds’ — those willing to cooperate,” explained Lindenstrauss. “But the SDF maintains ties with the Kurdish insurgency in Turkey, which has long called for independence for Turkey’s Kurdish minority. That makes the arrangement problematic for Ankara.

“Even now, after the agreement was signed, it remains unclear whether the SDF will disband or continue operating with some level of autonomy. They’re a large, well-armed militia controlling significant territory. It’s not clear why they would give that up voluntarily.”

Beyond the Kurdish question, Syria’s tilt toward Turkey has sparked anxiety among other minority communities. Some fear a resurgence of political Islam in the country, which now dominates in Turkey, and possible persecution of non-Sunni groups.

An Alawite citizen in Syria, a member of a sect that split from mainstream Islam and who requested anonymity due to concerns for his safety, told The Times of Israel: “This relationship with Turkey isn’t good. If Syria stays under Turkish influence, it will lead to the spread of political Islam.

“I believe Erdogan has a vision to restore the Ottoman Empire and dominate the Middle East,” he said. “A closer relationship with Saudi Arabia, a more moderate Sunni Arab power, would be a better path for Syria.”